August Theme of the Month: Differentiated Instruction

- Contemporary student populations are becoming increasingly academically diverse (Gable et al., 2000; Guild, 2001; Hall, 2002; Hess, 1999; McAdamis, 2001; McCoy and Ketterlin-Geller, 2004; Sizer, 1999; Tomlinson, 2004a; Tomlinson, Moon, and Callahan, 1998).

- The inclusion of students with disabilities, students with language backgrounds other than English, students with imposing emotional difficulties and a noteworthy number of gifted students, reflect this growing diversity (Mulroy and Eddinger, 2003; Tomlinson, 2001b, 2004a).

- Learning within the inclusive classroom is further influenced by a student’s gender, culture, experiences, aptitudes, interests and particular teaching approaches (Guild, 2001; Stronge, 2004; Tomlinson, 2002, 2004b).

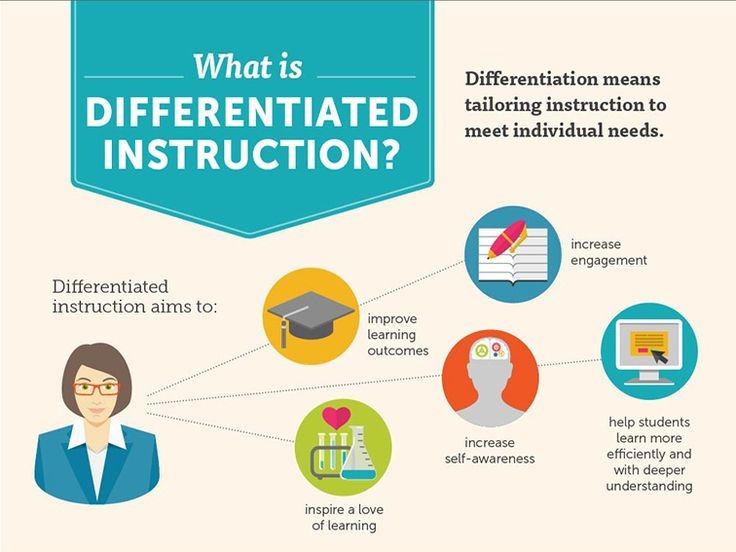

- Tomlinson (2005), a leading expert in this field, defines differentiated instruction as a philosophy of teaching that is based on the premise that students learn best when their teachers accommodate the differences in their readiness levels, interests and learning profiles. A chief objective of differentiated instruction is to take full advantage of every student’s ability to learn (Tomlinson, 2001a, 2001c, 2004c, 2005).

- Tomlinson (2000) maintains that differentiation is not just an instructional strategy, nor is it a recipe for teaching, rather it is an innovative way of thinking about teaching and learning.

- Contemporary classrooms should accept and build on the basis that learners are all essentially different (Brighton, 2002; Fischer and Rose, 2001; Griggs, 1991; Guild, 2001; Tomlinson, 2002).

- Research supports the view that curricula should be designed to engage students, it should have the ability to connect to their lives and positively influence their levels of motivation (Coleman, 2001; Guild, 2001; Hall, 2002; Sizer, 1999; Strong et al., 2001).